History of Japan

From jeena

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Japan |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Music and performing arts |

The first permanent capital was founded at Nara in 710, which became a center of Buddhist art, religion and culture. The current imperial family emerged about 700, but until 1868 (with few exceptions) had high prestige but little power. By 1550 or so political power was subdivided into several hundred local units, or "domains" controlled by local "daimyō" (lords), each with his own force of samurai warriors. Tokugawa Ieyasu came to power in 1600, gave land to his supporters, set up his "bakufu" (military government) at Edo (modern Tokyo). The "Tokugawa period" was prosperous and peaceful, but Japan deliberately terminated the Christian missions and cut off almost all contact with the outside world.

In the 1860s the Meiji period began, and the new national leadership systematically ended feudalism and transformed an isolated, underdeveloped island country into a world power that closely followed Western models. Democracy was problematic, because Japan's powerful military was semi-independent and overruled—or assassinated—civilians in the 1920s and 1930s. The military moved into China starting in 1931 and declared all-out war on China in 1937. Japan controlled the coast and major cities and set up puppet regimes, but was unable to defeat China. Its attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 led to war with the United States and its allies. After a series of naval victories by mid-1942, Japan's military forces were overextended and its industrial base was unable to provide the needed ships, armaments and oil. Even with his navy sunk and his main cities destroyed by air, the Emperor held out until August 1945 when two atomic bombs and a Soviet invasion forced a surrender.

Occupied by the U.S. after the war and stripped of its entire empire, Japan was transformed into a peaceful and democratic nation. After 1950 it enjoyed very high economic growth rates, and became a world economic powerhouse, especially in engineering, automobiles and electronics. Since the 1990s economic stagnation has been a major issue, with an earthquake and tsunami in 2011 causing massive economic dislocations and loss of the nuclear power supply.

Contents

|

Japanese prehistory

Paleolithic Age

Main article: Japanese Paleolithic

The Japanese Paleolithic age covers a lengthy period starting as early as 50,000 BC and ending sometime around 12,000 BC, at the end of the last ice age.

Artifacts claimed to be older than ca. 38,000 BC are not generally

accepted, and most historians therefore believe that the Japanese

Paleolithic started after 40,000 years ago.[2]The Japanese archipelago would become disconnected from the mainland continent after the last ice age, around 11,000 BC. After a hoax by an amateur researcher, Shinichi Fujimura, had been exposed,[3] the Lower and Middle Paleolithic evidence reported by Fujimura and his associates has been rejected after thorough reinvestigation.

As a result of the fallout over the hoax, now only some Upper Paleolithic evidence (not associated with Fujimura) can possibly be considered as having been well established.

Ancient Japan

Jōmon period

Main article: Jōmon period

The Jōmon period

lasted from about 14,000 until 300 BC. The first signs of civilization

and stable living patterns appeared around 14,000 BC with the Jōmon

culture, characterized by a Mesolithic to Neolithic semi-sedentary hunter-gatherer lifestyle of wood stilt house and pit dwellings and a rudimentary form of agriculture.Weaving was still unknown at the time and clothes were often made of furs. The Jōmon people started to make clay vessels, decorated with patterns made by impressing the wet clay with braided or unbraided cord and sticks. Based on radio-carbon dating, some of the oldest surviving examples of pottery in the world can be found in Japan along with daggers, jade, combs made of shells, and various other household items dated to the 11th millennium BC.[4]

The most recent finds, in 1998, have been at the Odai Yamamoto I site, where fragments of a single vessel are dated to 14,500 BC (ca 16,500 BP); this places them as or among the earliest pottery currently known.[5][6][7] Among older discoveries, calibrated radiocarbon measures of carbonized material from pottery artifacts: Fukui Cave 12500 ± 350 BP and 12500 ± 500 BP (Kamaki & Serizawa 1967), Kamikuroiwa rock shelter 12, 165 ± 350 years BP in Shikoku.[8] although the specific dating is disputed.

Elaborate pottery figurines known as dogū are found from the Late Jōmon period.

Yayoi period

Main article: Yayoi period

The start of the Yayoi period marked the influx of new practices such as weaving, rice farming, and iron and bronze making. Bronze and iron appear to have been simultaneously introduced into Yayoi Japan. Iron was mainly used for agricultural and other tools, whereas, bronze was used for ritual and ceremonial artifacts. Some casting of bronze and iron began in Japan by about 100 BC, but the raw materials for both metals were introduced from the Asian continent. The Yayoi period brought Shamanism and divination by oracles to Shinto, in order to guarantee good crops.,[9]

Japan first appeared in written records in 57 AD with the following mention in China's Book of the Later Han:[10] "Across the ocean from Lelang are the people of Wa. Formed from more than one hundred tribes, they come and pay tribute frequently." The book also recorded that Suishō, the king of Wa, presented slaves to the Emperor An of Han in 107. The Sanguo Zhi, written in the 3rd century, noted that the country was the unification of some 30 small tribes or states and ruled by a shaman queen named Himiko of Yamataikoku.

During the Han and Wei dynasties, Chinese travelers to Kyūshū recorded its inhabitants who claimed that they were the descendants of the Grand Count (Tàibó) of the Wu.[citation needed] The inhabitants also show traits of the pre-sinicized Wu people with tattooing, teeth-pulling, and baby-carrying. The Sanguo Zhi records the physical descriptions which are similar to ones on haniwa statues, such as men wearing braided hair and tattoos and women wearing large, single-pieced clothing.

The Yoshinogari site in Kyūshū is the most famous archaeological site of the Yayoi period and reveals a large settlement continuously inhabited for several hundred years. Archaeological excavation has shown the most ancient parts to be from around 400 BC. It appears that the inhabitants had frequent communication and trade relations with the mainland. Today, some reconstructed buildings stand in the park on the archaeological site.[11]

Kofun period

Main article: Kofun period

The Kofun period began around 250 AD, is named after the large tumulus burial mounds (kofun) that started appearing around that time.The Kofun period (the "Kofun-Jidai") saw the establishment of strong military states, each of them concentrated around powerful clans (or zoku). The establishment of the dominant Yamato polity was centered in the provinces of Yamato and Kawachi from the 3rd century AD till the 7th century, establishing the origin of the Japanese imperial lineage. And so the polity, by suppressing the clans and acquiring agricultural lands, maintained a strong influence in the western part of Japan.

Japan started to send tributes to Imperial China in the 5th century. In the Chinese history records, the polity was called Wa, and its five kings were recorded. Based upon the Chinese model, they developed a central administration and an imperial court system, with its society being organized into various occupation groups. Close relationships between the Three Kingdoms of Korea and Japan began during the middle of this period, around the end of the 4th century.

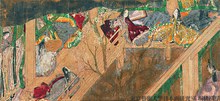

Classical Japan

Asuka period

Main article: Asuka period

During the Asuka period

(538 to 710), the proto-Japanese Yamato polity gradually became a

clearly centralized state, defining and applying a code of governing

laws, such as the Taika Reforms and Taihō Code.[12] Also during the same period, the Japanese developed strong economic ties with the Paikche or Baekje

people, who lived on the southwestern coast of the Korean Peninsula.

Good relations with the Baekje had begun in 391 when a Japanese

expedition saved the King of Baekje and the Baekje people from their

traditional enemies—the Koguryo people—who lived in the northern part of the Korean Peninsula.[13]Indeed, Buddhism was introduced to Japan in 538 by Baekje people, to whom Japan continued to provide military support.[14] In Japan, however, Buddhism was promoted largely by the ruling class for their own purposes[citation needed]. Accordingly, in the early stages, Buddhism was not a popular religion with the common people of Japan.[15] However, the introduction of Buddhism led to a discontinuing of the practice of burying deceased people in large kofuns.

Prince Shōtoku came to power in Japan as Regent to Empress Suiko in 594. Empress Suiko had come to the throne as the niece of the previous Emperor—Sujun (588–593)--who had been assassinated in 593. Empress Suiko had also been married to a prior Emperor—Bidatsu (572–585), but she was the first female ruler of Japan since the legendary matriarchal times.[16]

As Regent to Empress Suiko, Prince Shotoku devoted his efforts to the spread of Buddhism and Chinese culture in Japan.[16] He is also credited with bringing relative peace to Japan through the proclamation of the Seventeen-article constitution, a Confucian style document that focused on the kinds of morals and virtues that were to be expected of government officials and the emperor's subjects. Buddhism would become a permanent part of Japanese culture.

A letter brought to the Emperor of China by an emissary from Japan in 607 stated that the "Emperor of the Land where the Sun rises (Japan) sends a letter to the Emperor of the land where Sun sets (China)",[17] thereby implying an equal footing with China which angered the Chinese emperor.[18]

Nara period

Main article: Nara period

The Nara period

of the 8th century marked the emergence of a strong Japanese state and

is often portrayed as a golden age. In 710, the capital city of Japan

was moved from Asuka to Nara.[19]

Hall (1966) concludes that "Japan had been transformed from a loose

federation of uji in the fifth century to an empire on the order of

Imperial China in the eighth century. A new theory of state and a new

structure of government supported the Japanese sovereign in the style

and with the powers of an absolute monarch."[20]

Traditional, political, and economic practices were now organized

through a rationally structured government apparatus that legally

defined functions and precedents. Lands were surveyed and registered

with the state. A powerful new aristocracy emerged. This aristocracy

controlled the state and was supported by taxes that were efficiently

collected. The government built great public works, including government

offices, temples, roads, and irrigation systems. A new system of land

tenure and taxation, which was designed to widely spread land ownership

throughout the rural population, was introduced. Such allotments tended

to be about one acre. However, they could be as small as one-tenth of an

acre. However, lots for slaves were about two-thirds the size of the

allotments to free men. Allotments were reviewed every five years when

the census was conducted.[21]There was a cultural flowering during this period.[19] Soon, dramatic new cultural manifestations characterized the Nara period, which lasted four centuries.[22]

Following an imperial rescript by Empress Gemmei, the capital was moved to Heijō-kyō, present-day Nara, in 710. The city was modeled on Chang'an (now Xi'an), the capital of the Chinese Tang Dynasty.

During the Nara Period, political development was marked by a struggle between the imperial family and the Buddhist clergy,[21] as well as between the imperial family and the regents—the Fujiwara clan. Japan did enjoy peaceful relations with their traditional foes—the Silla people—who occupied the southeast coast of the Korean Peninsula. Japan also established formal relationships with the Tang dynasty of China.[23]

In 784, the capital was again moved to Nagaoka-kyō to escape the Buddhist priests; in 794, it was moved to Heian-kyō, present-day Kyōto. The capital was to remain in Kyoto until 1868.[24] In the religious town of Kyoto, Buddhism and Shinto began to form a syncretic system.[25]

Historical writing in Japan culminated in the early 8th century with the massive chronicles, the Kojiki (The Record of Ancient Matters, 712) and the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan, 720). These chronicles give a legendary account of Japan's beginnings, today known as the Japanese mythology. According to the myths contained in these chronicles, Japan was founded in 660 BC by the ancestral Emperor Jimmu, a direct descendant of the Shintō deity, Amaterasu (Sun Goddess). The myths recorded that Jimmu started a line of emperors that remains to this day. Historians assume that the myths partly describe historical facts, but the first emperor who actually existed was Emperor Ōjin, though the date of his reign is uncertain. Since the Nara period, actual political power has not been in the hands of the emperor but has, instead, been exercised at different times by the court nobility, warlords, the military, and, more recently, the Prime Minister of Japan.

Heian period

Main article: Heian period

Strong differences from mainland Asian cultures emerged (such as an indigenous writing system, the kana). Due to the decline of the Tang Dynasty,[29] Chinese influence had reached its peak, and then effectively ended, with the last imperially sanctioned mission to Tang China in 838, although trade expeditions and Buddhist pilgrimages to China continued.[30]

The end of the period saw the rise of various military clans. The four most powerful clans were the Minamoto clan, the Taira clan, the Fujiwara clan, and the Tachibana clan. Towards the end of the 12th century, conflicts between these clans turned into civil war, such as the Hōgen (1156–1158). The Hogen Rebellion was of cardinal importance to Japan, since it was the turning point that led to the first stages of the development of feudalism in Japan.[35] The Heiji Rebellion of 1160 also occurred during this period[36] and the uprising was followed by the Genpei War, from which emerged a society led by samurai clans under the political rule of the shōgun--the beginnings of feudalism in Japan.

No comments:

Post a Comment